By Luke Munford and Doriane Mignon[1]

Background

The UK experiences some of the widest regional inequalities among OECD countries. This is particularly reflected in measures of health and economic productivity. For example, using the most recent data published by the Office for National Statistics it can be seen that the average Gross Value Added (GVA) per hour worked was £34.00 in the North East and £36.80 in the North West, compared to £44.40 in the South East and £50.60 in London. This means that the GVA per hour worked in the North West was 27% lower than in London and 17% lower than in the South East.

The Productivity Institute’s regional scorecards, which include a variety of productivity-related metrics, reveal that in the North West, 36.3% of people not in the labour market are not seeking work due to illness. In the South East, ‘only’ 25.9% of those not active in the labour market are not seeking work due to illness. There are clear patterns; regions with lower levels of economic productivity have higher rates of illness and poor health.

Indeed, a 2018 report by the Northern Health Science Alliance (NHSA) showed that around 30% of the ‘productivity gap’ between the Northern regions of England and the rest of the country was attributable to poorer health outcomes in the North. The report concluded that reducing these gaps in health could increase productivity in the North (and hence the whole of England) by around £13.2bn per year. However, the report was limited to using crude measures of health including rates of mortality and morbidity.

In our latest work, we extend the analysis in a number of ways. Most importantly we use very granular measures of economic prosperity and health by location. We are particularly interested in how population mental health is associated with economic activity, particularly household income and economic productivity. Our hypothesis is that poor mental health limits labour force participation and prosperity, which potentially contributes to exacerbating economic disparities. We think this relationship could operate through two potential channels: 1) people with low levels of mental health are less likely to enter the labour market and 2) people with low levels of mental health are more likely to show absenteeism or presenteeism at work.

What we do

To examine if there is a relationship between population mental health and economic prosperity, we combine location-specific data from various sources. We use the ‘middle layer super output area’ (MSOA) as our unit of analysis. MSOAs are statistical geographies that typically have a population of between 5,000 and 15,000 people in 2,000 to 6,000 households. There were 7,201 MSOAs in England based on the 2011 Census.[2] Our analysis only considers the period from 2011 to 2019. We deliberately decided to stop before 2020 due to widespread shocks to both population mental health and economic outcomes.

To measure population mental health, we use the Small Area Mental Health Index (SAMHI), a composite index including information on the number of hospital admissions due to mental health related conditions, the number and type of antidepressant prescriptions, the prevalence of GP diagnosed depression, and benefit claims related to mental illness. We measure economic prosperity in two ways: first using Gross Disposable Household Income (GDHI) and secondly using Gross Value Added (GVA) per capita[3].

We use a statistical approach to model the relationship between mental health (our key ‘predictor’ variable) and our two measures of economic prosperity (our key outcomes). We account for factors that could influence this relationship, such as the population size of each MSOA and the age composition of the population. We employ a statistical technique that also allows us to account for unobservable area-specific factors.

There is an argument that, apart from mental health impacting on prosperity, the causality could also be the reverse with economic prosperity affecting mental health. To partially overcome this, we use the one-period-lag of mental health such that the mental health in one year is associated with the economic prosperity the following year.

As well as looking at the national picture, we explore whether the strength of the relationship between mental health and economic prosperity differs by region.

What we find

There are strong regional variations and temporal trends in both population mental health and economic prosperity, consistent with the TPI scorecards.

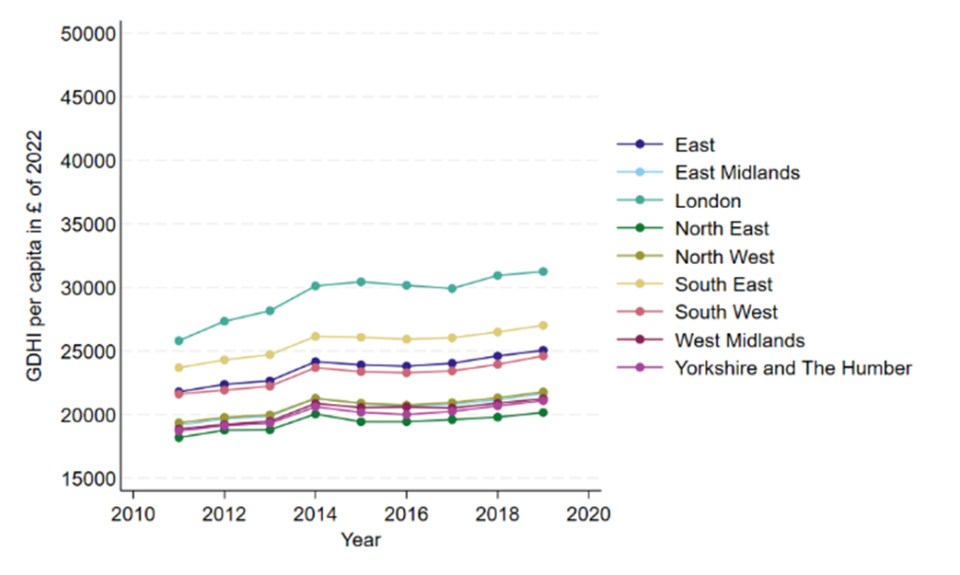

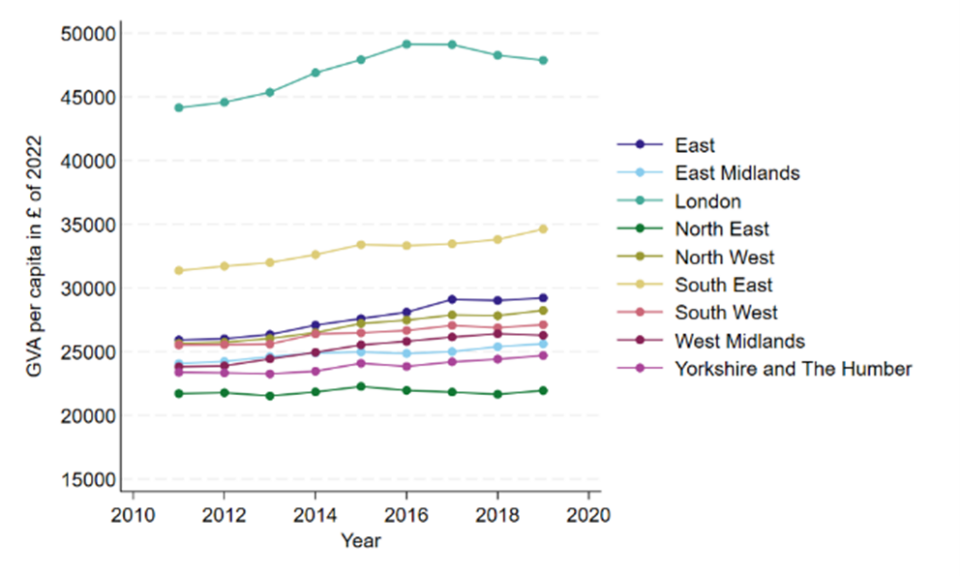

Regions such as London and the South East consistently outperform others in productivity, while the North East and North West lag behind. Whilst all regions have seen an increase in household income, the gaps, especially relatively to London, have remained quite wide (Figure 1). For productivity, the regional gaps relative to London have somewhat narrowed but also remain quite wide (Figure 2).[4]

Figure 1: Trends over time in Gross Disposable Household Income (GDHI), by region

Figure 2: Trends over time in Gross Value Added (GVA) per-capita, by region

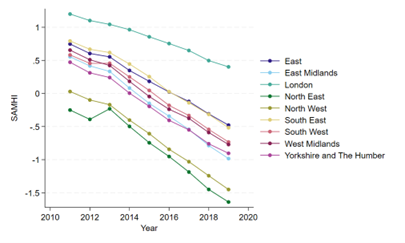

Across all regions, mental health has generally worsened, but at a quicker rate in the North East and North West, the two regions with consistently the lowest levels of mental health (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Trends over time in mental health (measured using the Small Area Mental Health Index; SAMHI), by region

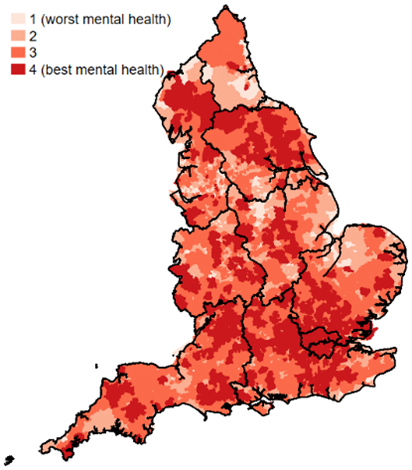

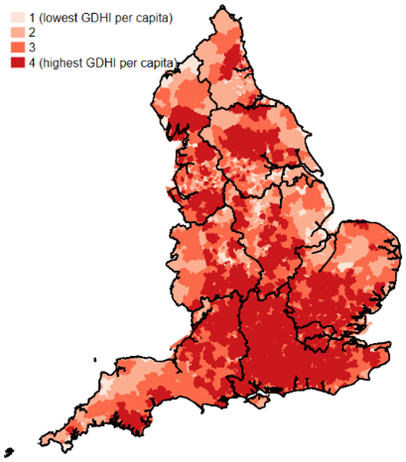

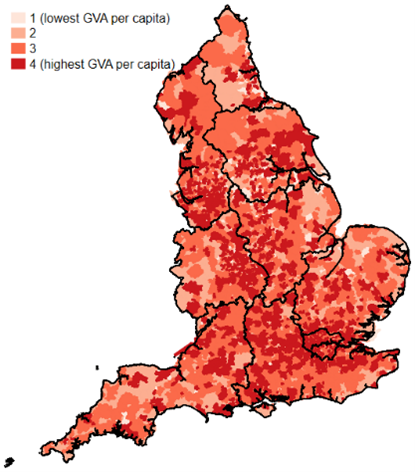

The heat maps in Figure 4 (data for 2019) suggest that regions with higher economic prosperity also show higher levels of population mental health, and our statistical analysis suggests a strong correlation. Clusters of areas, mostly in and around London and the South East, have the best mental health and best economic outcomes. There are some interesting hotspots in other parts of the country, such as some of the other big cities including Manchester and Birmingham as well as some rural areas in North Yorkshire.

Importantly, we demonstrate a particularly strong and statistically significant relationship between population mental health and household income. In our preferred statistical model using the data at the MSOA level, a one standard deviation increase in population mental health (proxied by the SAMHI) is associated with a 1.9% increase in gross disposable household income, equivalent to £439 per year, or around £24.7 billion per year at the national level.

Figure 4: Heat maps of population mental health (left) GDHI (centre) and GVA per-capita (right) in 2019

| Panel (a): Small Area Mental Health Index (SAMHI) | Panel (b): Gross Disposable Household Income (GDHI) | Panel (c): Gross Value Added (GVA) per-capita |

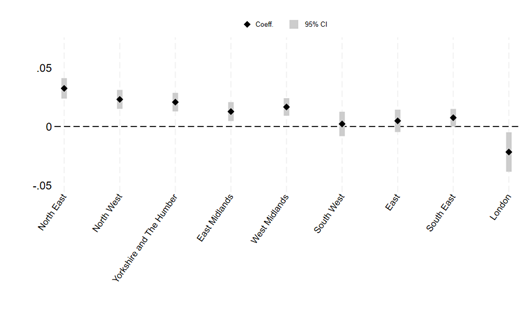

When drilling down to individual regions, there is substantial variation in the strength of the relationship (Figure 5). For the North East, the model implies that a one standard deviation increase in population mental health increased GDHI by around 3.2% (p<0.001), which is equivalent to £739 per year per capita. For the North West, the model implies that a one standard deviation increase in population mental health increased GDHI by around 2.3% (p<0.001), equivalent to £531 per year per capita.

Applying estimates for population and household size, these estimate scale to be:

- Increasing population mental health by one standard deviation in the North West will increase GDHI by £3.9bn per year

- Increasing population mental health by one standard deviation in the North East will increase GDHI by £2bn per year

Figure 5: The effect of mental health on GDHI, by regions

Policy Implications

Our research has a number of policy implications.

First, with regard to regional development, investment to improve mental health care strategies should be integral to policies aimed at reducing economic disparities between places. Regions with the most significant mental health challenges, like the North East and North West, stand to benefit the most from such interventions. Granular measures of SAMHI, GDHI and GVA at super local level can help to identify specific place-based and contextual factors and target interventions, helping to prioritise mental health care funding where it is most needed and raising the effectiveness of such interventions.

Second, mental health should become a much more important factor in framing the productivity narrative, especially in terms of it being a driver of more productive worker performance, rather than just a good health outcome. To raise workforce participation and reduce absenteeism and presenteeism, businesses should address mental health care issues of their workforce both in terms of prevention and facilitating return to work, and help contribute to resolving the UK productivity puzzle.

[1] We thank Clare Bambra, Nicky Cullum, Sam Khavandi and Matt Sutton for collaboration on this topic and the accompanying academic paper (currently under review)

[2] Due to differences in health care financing and devolution, we restrict our analysis here to England. We plan to look at other home nations in due time.

[3] We proxy productivity by per capita income and ignore differences between share of working population and workforce participation.

[4] We conducted the analysis for the period up to and including 2019, that is, before the start of the pandemic. See the Figures in The Productivity Institute’s regional scorecards for date from 2020 onwards.