Productivity plans for local government: more than just reducing expenditure

A recently announced funding package for local government comes with the requirement for local authorities to produce ‘productivity plans’ for submission to central government. In this blog, Owen Garling, Knowledge Transfer Facilitator at the Bennett Institute for Public Policy and lead for the East Anglia Regional Productivity Forum, considers the lessons that local government can learn from The Productivity Institute’s work on public sector productivity.

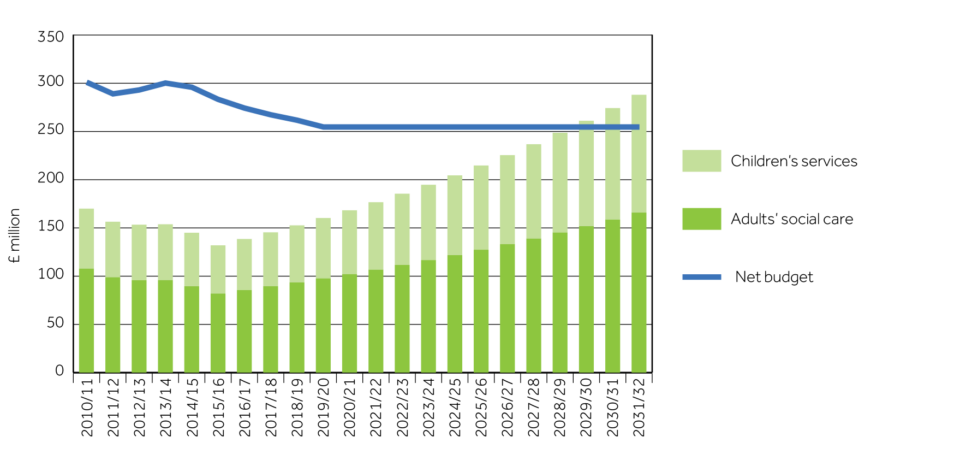

Working in local government a decade ago, there was a particular chart that was often passed round teams in the same way that scurrilous notes would be passed around classrooms. The so-called ‘Barnet Graph of Doom’ set out how the cost pressures associated with adult and children’s social care services would eventually consume the total budget of the council, leaving no funding for the other services that councils provide to their communities.

Source: Capitalising on the Boroughs: promoting growth through greater financial devolution in London. A report from the Society of London Treasurers.

And whilst the chart was first drawn a decade ago, in many ways it foresaw today’s financial environment which – following a real term reduction in funding of 52.3 per cent in the decade between 2010-11 and 2020-21 – has seen an increasing number of local authority finance officers issuing Section 114 notices setting out that they believe that the authority is about to incur unlawful expenditure according to the 1988 Local Government Finance Act.

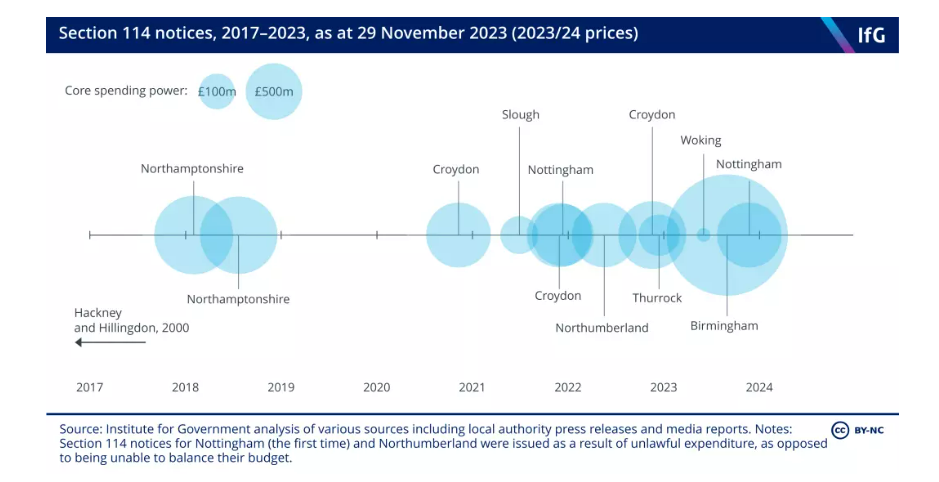

As the following chart produced by the Institute for Government shows, the frequency of Section 114 notices being issued has increased over the last five years.

Source: Institute for Government. Local government section 114 (bankruptcy) notices

It is against this backdrop that over 40 MPs recently called for an increase in funding to local authorities. In response to this call, the Secretary of State for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Michael Gove, provided a written statement updating parliament on local government financing.

Gove’s announcement set out plans to provide an additional £600 million of funding for local government to be distributed across the sector, including £500 million of new ring-fenced funding for councils responsible for the provision of adults and children’s social care.

In his statement, Gove stressed the need for further work to be done to “improve productivity in local government, as part of our efforts to return the sector to sustainability in the future” and announced that local authorities would be required to produce productivity plans “setting out how they will improve service performance and reduce wasteful expenditure to ensure every area is making the best use of taxpayers’ money.”

Whilst the written statement provides some high-level details about the productivity plans – more information is forthcoming, an expert panel will be established, the plans will be used to inform future funding settlements – there is little detail yet of what should be included in these plans.

Productivity in the public sector

When it comes to the public sector, the concept of productivity is one that is viewed with some concern and caution, with some seeing productivity as being analogous with efficiency savings and service reductions.

For those who have worked in, or with, the local government sector, the idea of productivity plans may smack of previous initiatives dating back to the army of armchair auditors that Lord Pickles, then Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government, the precursor to DLUHC, threatened to unleash on the sector.

Indeed, the focus on “wasteful expenditure” and “service performance” in Gove’s announcement may mean that these plans are indeed a continuation of the efficiency drive that local government has had to implement given its reduction in core funding over the last decade.

But what if we think about public sector productivity as being about more than just the efficiency of services?

As a chapter in The Productivity Institute’s recently published The Productivity Agenda argues, “focussing exclusively on efficiency and cost savings has not always worked in the past, since it carries risks such as poor service quality, low staff retention and underinvestment in innovation.”

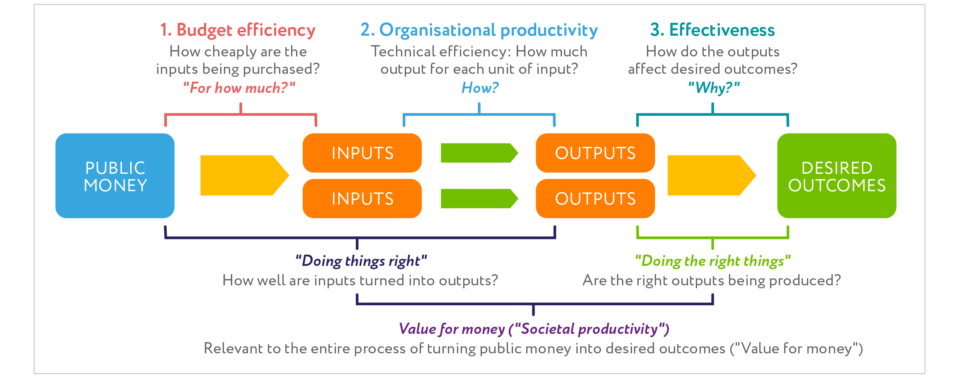

The Productivity Institute’s work, as originally set out in the Making Public Sector Productivity Practical report published in partnership with Capita, argues that a broader conceptualisation of public sector productivity needs to be developed that considers three key components – budgetary efficiency (for how much?), organisational productivity (how?), and effectiveness (why?) – all of which are connected through the public sector delivery chain as set out in the following diagram taken from The Productivity Agenda.

Source: The Productivity Agenda 2023. Figure adapted from Aldridge, S., Hawkins, A., & Xuereb, C (2016). Improving Public Sector Efficiency to Delivery a Smarter State.

What’s particularly important about this approach is the ways in which this model helps to differentiate between efficiency – what the management thinker Peter Drucker called “doing things right” – and effectiveness – “doing the right things” – and provides a framework against which local authorities could map both existing measures and identify areas where further development is required to ensure that they have a clear understanding of effectiveness along the whole length of the delivery chain.

Running the length of the delivery chain, The Productivity Institute’s work also identifies three main areas on which pro-productivity policies can be focused:

- Adaptive organisational design – adaptive organisations are able to respond to changes in their operating environment. In many ways, local government has had to be adaptive given the profound changes in its operating environment, but perhaps more time should be dedicated to longer-term strategic planning.

- Technology and continuous innovation – technological innovation can transform the way that things are done, and in particular free up the precious time of public sector workers to focus on those tasks that require a human touch.

- An agile workforce – An organisation is nothing without its workforce, and this is particularly true of local government. However, to enable the other two key areas to function requires the appropriate set of skills across the public sector.

And whilst none of this should be particularly new for colleagues working in local government, perhaps the creation of productivity plans should be seen as more than purely a way of reducing what some may see as “wasteful expenditure.” Could productivity plans provide both national and local government with a key tool to help deepen their collective understanding of how the productivity puzzle plays out across the public sector, and key ways in which it can be tackled?