No post-pandemic productivity boost in sight

An analysis of the Q3-2021 Flash Estimates of Productivity for the UK by the Office for National Statistics by Bart van Ark, Managing Director, The Productivity Institute & Professor of Productivity Studies, University of Manchester.

UK productivity growth dropped by 1.2 percent in Q3 over Q2, bringing the productivity level down to just 0.5 percentage above the 2019 level

Key observations for the outlook on productivity for 2022

- The drop in aggregate output per hour by 1.2 percent from July-September 2021 (Q3-21) compared to the previous quarter (Q2-2021) shows that the post-pandemic recovery of low-productivity sectors is still impacting on the productivity aggregate.

- The productivity growth rate within sectors increased at 0.5 percent on average over the previous quarter, which is close to the pre-pandemic productivity trend of about 0.4 percent.

- The level of output per hour worked in Q3-21 was also 0.5 percent above the average of 2019 (year as whole), indicating that the elevated productivity level during the pandemic is now more or less back at what it would have been if the pandemic had not occurred.

- Eightteen out of the 26 sectors showed productivity levels above those of 2019, suggesting that short-term recovery effects are likely to peter out over the next one or two quarters.

- The latest figures lead to caution with regard to the productivity outlook for 2022 and beyond. There is no post-crisis productivity boom in near sight, suggestion that various positive and negative factors impacting on productivity are partly offsetting each other.

Summary of the data from the Office of National Statistics

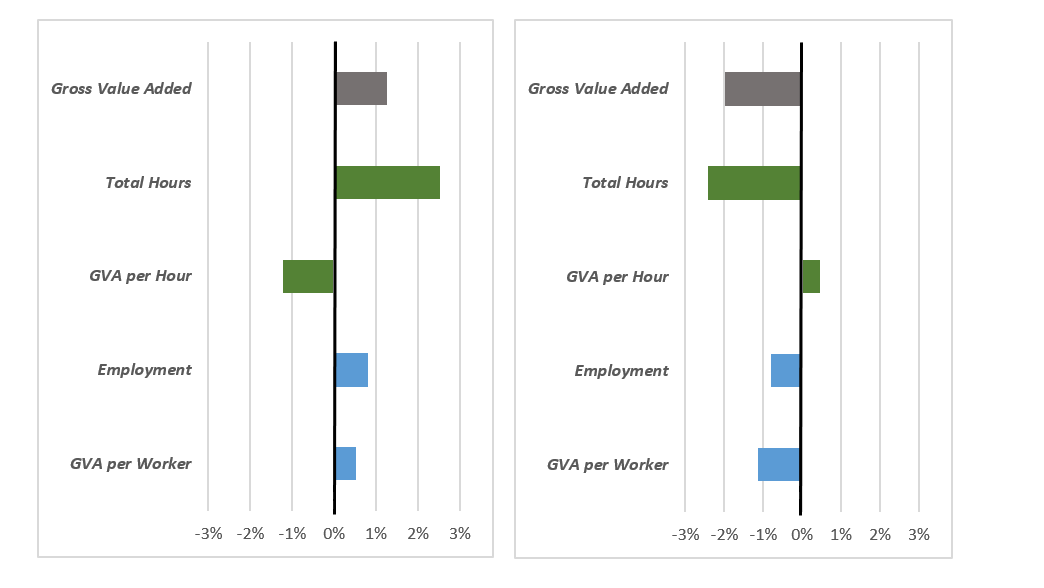

Labour productivity, measured as gross value added per hour, declined by 1.2 percent during the third quarter of 2021 (Q3-21) compared to the second quarter (Q2-21) according to the latest estimates by the Office of National Statistics, UK productivity flash estimate: July to October 2021 (16 November 2021). This decline reflects a modest increase in output (gross value added) at 1.3 percent relative to a stronger much increase in working hours at 2.5 percent.

The fall in hourly productivity in Q3-21 is entirely due to the on-going recovery in output and employment in sectors, such as hotels & catering and recreation & culture, which suffered most from the lockdowns. In fact, the reopening of those sectors which are characterised by relatively low levels of labour productivity, caused economy-wide productivity to fall by 1.7 percent during Q3-21. This which was only partially offset by an average 0.5 percent *true” productivity growth (that is, after removing the reallocation effects) within individual sectors.

Compared to the pre-pandemic period, output per hour is now just 0.5 percent above the average level for 2019. However, output, hours and employment are still well below the 2019 level which suggests that the recovery has not been fully completed (see Panel B of the Chart). Low productivity sectors are therefore likely to continue to weigh on productivity for at least another one or two more quarters.

Output, Labour Input and Productivity, Q3-21 (July-September), in %

PANEL A: Q3-21 over Q2-21 (April-June) PANEL B: Q3-21 over average of 2019

Source: Office of National Statistics, UK Productivity flash estimate: July to October 2021, 16 November 2021.

Out of the 26 individual sectors, which together accounted for an average increase of 0.5 percent within-sector productivity in Q3-21 over Q2-21, 18 sectors showed rising productivity while eight industries experienced a decline.

- Of the ten manufacturing industries, six industries showed positive productivity growth rates in Q3-21 over Q2-21, with some of the fastest increases in “manufacturing of wood & paper products & printing” (5.5%), “manufacture of chemicals, chemical & pharmaceutical products” (5%), and “manufacture of transport equipment” (3.3%). It should be noted, however, that the transport equipment industry, has still not fully recovered from a 14 percent drop in output per hour between Q3-20 and Q2-21.

- Four manufacturing industries experienced a productivity decline, including “manufacturing of computer, electronic, optical & electrical products” (-2.4%) and “manufacturing of computer, electronic, optical & electrical products” (-2.2%). This could point at the possible impact of supply chain shortages. Both industries have not yet fully recovered from a decline in output per hour since Q3-20.

- Relatively large drops in productivity in Q3-21 were also observed in “construction” (-3.3%) and “wholesale and retail trade” (-5.1%), reflecting increases in hours worked which outpaced the rise in output during the past quarter. Strong within-sector productivity improvements were seen in “accommodation & food services” (3.4%) and in “arts, entertainment & recreation” (3.1%) following the reopening of the sectors from the COVID-19 lockdowns.

While there clear signs of labour shortages emerging from the ONS Labour market overview, November 2021 showing a record increase in vacancies across the economy, we do not yet see an impact of those shortages on aggregate productivity growth. Total hours worked have risen by on average 2.5 percent in Q3-21 compared to Q2-21, although much of this was driven by the return to work in “accommodation & food services” (25.8%) and in “arts, entertainment & recreation” (16%). In contrast, total hours worked declined by 1% in both manufacturing and in “information and communication”, and the past quarter’s productivity improvements in those sector have been quite modest at 0.8% for manufacturing and 1.1% for “information and communication”.

Outlook for productivity

The numbers from the latest ONS releases in combination with forecasts from the National Institute Monthly GDP Tracker (November 2021) and the National Institute UK Economic Outlook together point at a weaker outlook for productivity growth in 2022 and beyond compared to what was expected a quarter ago. Even as the negative impact from the reopening of lower productivity sectors will peter out over the coming quarters, the projections point at a flatlining OF labour productivity growth to zero percent in 2022. Beyond 2022 labour productivity might return to between 0.5 percent per year (which more or less equals the pre-pandemic trend) and 1 percent (if significant upsides emerge from technological change and innovation).

A wide range of factors are impacting on any outlook for productivity growth, several of which may have opposite effects and thereby partly offsetting each other:

- The long shadow of the pandemic has put businesses on alert with regard to their outlook. The immediate recovery effects of previous infection waves are gradually petering out. The risk of new virus variants or declining vaccine effectiveness may possibly lead to a new wave of high infection rates. This could impact productivity through another slowdown in demand and potential business closures – all depending on the extent to which employment and business support programmes can or will be revived.

- So far, there is not much evidence of strong effects from labour market scarring on productivity. Furlough funding and loan guarantees have provided significant protection regarding employee well-being and future investments intentions, which helped companies avoid large setbacks in reviving their business. See TPI working paper on Covid-19 business support and SME productivity in the UK (July 2021). However, some of the scarring effects may only appear over time, such as early retirement decisions of many older workers, the impact on interrupted education on the skills of young people, and a rise in inequality as particular segments of workers (e.g. low skilled, or those marginally attached to the labour market) are finding it harder to get back into work.

- The rise in labour shortages across many industries and occupations has not yet been seen to constrain business performance, including productivity, very widely. Various forces are at work, including the ease with which firms can pass on wage and cost increases to consumers as well as the extent to which shortages can be filled by attracting workers from (possibly more productive) jobs elsewhere in the economy. The path towards higher productivity would come from higher wages incentivizing businesses to invest faster in automation, but this is proceeding at best gradually. See TPI blog on Labour shortages, productivity and incomes (November 2021).

- The challenges from supply chain constraints in the aftermath of the pandemic and the implementation of the Brexit deal may appear to be transitory, but the impact on prices and production shortfalls may have longer lasting effects. These effects may potentially cause businesses to cut down on production time or take inefficient sourcing decisions to secure continuity which could impact productivity growth for several quarters.

- More broadly the diffusion of new, in particular digital, technologies has accelerated during the COVID-crisis. There are signs that this may have left some positive impact on productivity growth during the pandemic. See TPI working paper on Productivity and the Pandemic: Short-Term Disruptions and Long-Term Implications (August 2021). However, the degree to which technology applications and innovations have helped firms below the productivity frontier to grow improve, or whether those have further strenghtened productivity growth of top performers is still unclear. The impact on productivity, and the distribution of the benefits across sectors and regions may be highly dependent on those trends.

Read Bart’s observations of previous estimates: