UK Regional Productivity: Insights from the 2025 ONS Sub-Regional Estimates

BART VAN ARK

The 2025 release of the UK sub-regional productivity estimates by the Office for National Statistics, covering data up to 2023, is a timely and welcome development. As the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic recedes, a clearer view of long-term regional productivity trends is beginning to take shape.

While large regional disparities in productivity levels persist, with London and the South East continuing to outperform the other regions and the national average, the latest data suggests some narrowing of regional gaps. Notably, the North West and Northern Ireland have recorded strong productivity growth since 2019. Yorkshire and the Humber, the East of England, and the South East have also shown robust post-pandemic performance. In contrast, Scotland, Wales, the Midlands, and the North East have experienced relatively weak productivity growth, indicating a mixed and uneven pattern of regional convergence.

The reasons behind London’s underperformance remain complex and somewhat unclear. Data limitations may be a contributing factor, as regional productivity estimates are derived from national-level output and employment data. However, these issues are unlikely to fully account for the observed decline in London’s productivity. A structural shift toward a predominantly lower-productivity services economy may be a contributing factor, particularly as the influence of high-productivity financial and business services appears to have diminished since the pandemic. Pandemic-related disruptions—especially in the transport sector, including public, private, and air travel—have also likely played a role.

Additionally, the rise in remote working may have had an impact, though its overall effect on productivity remains ambiguous. Many employees who live outside London may still hold London-based jobs and contribute to their firms’ output, complicating the picture. Moreover, existing research on the productivity effects of remote work is mixed and does not fully explain the scale of London’s recent decline. Interestingly, the strong performance of the South East and East of England may suggest some longer-term benefit from so-called “donut” effects, where economic activity shifts to surrounding regions.

Despite these challenges, the latest regional productivity estimates point to renewed potential for growth in several parts of the UK. The North West’s strong performance hints at the emergence of a new growth hub centred around its major cities. However, job creation in the region has not kept pace with productivity gains, raising important questions about the inclusivity of this growth. Ensuring that productivity improvements translate into broader economic opportunities will be key. The forthcoming Industrial Strategy White Paper is expected to provide further momentum for embedding a strong regional dimension into the UK’s growth agenda.

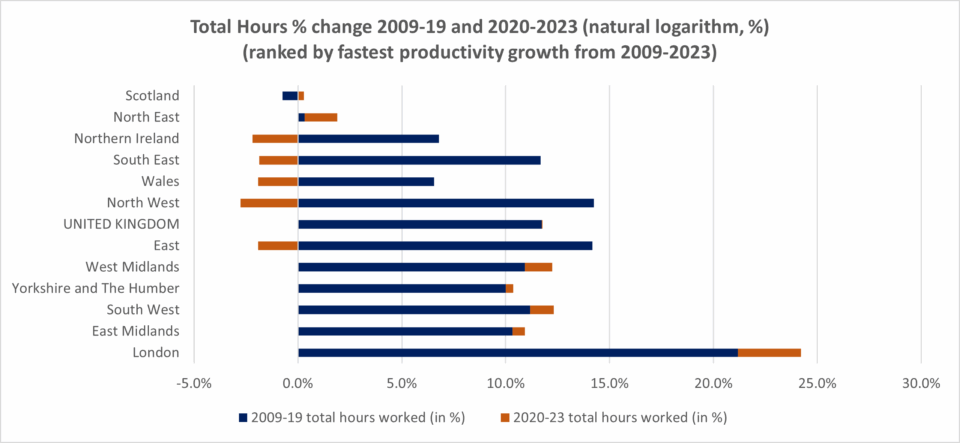

The two charts below illustrate cumulative changes in productivity and total hours worked by region, both before and after the pandemic. Chart 1 shows total productivity growth (measured as output per hour worked) from 2009–2019, along with additional growth from 2020–2023. Chart 2 presents the growth in total hours worked (“productivity hours”) over the same periods. Regions are ranked by overall productivity growth across the full period from 2008 to 2023.

Further details on regional productivity performance are available from The Productivity Institute, Regional Productivity Agenda (January 2025), and from TPI’s Productivity Lab website which includes several data animations and visualizations.

Note: Regions are ranked by overall productivity growth across the full period from 2008 to 2023.

Source: calculated from Office for National Statistics, Regional and subregional labour productivity, UK: 2023, 19 June 2025.