Is higher productivity at odds with improved wellbeing in post-pandemic Wales?

Professor Andrew Henley from Cardiff Business School is on the Executive Committee of The Productivity Institute and the lead for the Wales Productivity Forum.

The Well-being of Future Generations Act in Wales requires that long-term considerations of poverty, health inequalities and climate change are at the forefront of policy-making. Such goals could be at odds with productivity growth and traditional indicators of prosperity.

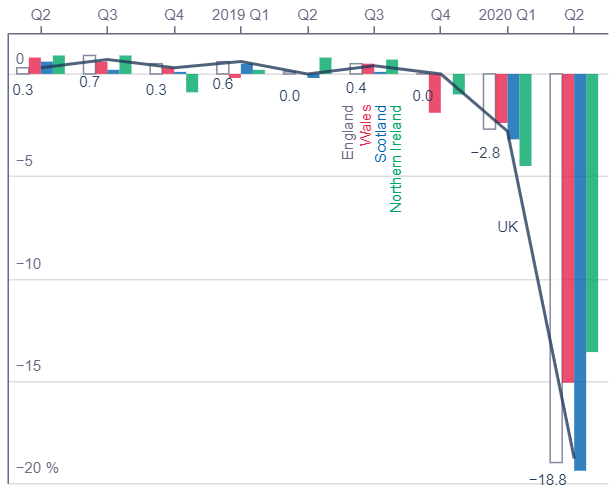

The economic impact of Covid-19 has been severe across the UK, with Wales no exception. Restrictions on business activity have meant furloughing thousands of employees, and this has had a negative effect on how much workers are able to produce – their ‘labour productivity’. In Wales, this may have compounded an already sizeable and widening gap with the rest of the UK. Wales has suffered from a wider productivity slowdown since the global financial crisis of 2007-09, and this has to date proved resistant to policy intervention.

An important policy in Wales is the 2015 ‘Well-Being of Future Generations (Wales) Act’ (or WFGA), supported by the creation of an independent Future Generations Commissioner. This act seeks to align policy objectives in Wales to a wider set of social and environmental wellbeing goals – away from a sole focus on material economic prosperity.

This could be at odds with the UK’s ‘levelling-up’ and productivity policy objectives, requiring Wales to occupy a different position as it balances the trade-off between efficiency and equity. But in practice, there is considerable scope within the Welsh approach to focus attention on inclusive and ‘clean’ economic growth, particularly as the nation begins to emerge from the pandemic.

The impact of the pandemic in Wales

Wales fared slightly better than England or Scotland in the early months of lockdown – see Figure 1. But it would be unwise to read too much into these differences or to suggest that is connected to the different approach of the Welsh Government. As in Scotland and Northern Ireland, whereas public health decisions have been devolved, business support has followed the same emergency levers developed by the UK government, with funding for those interventions derogated to Cardiff and disbursed through the Welsh Government and the Development Bank of Wales (Economic Intelligence Wales, 2020).

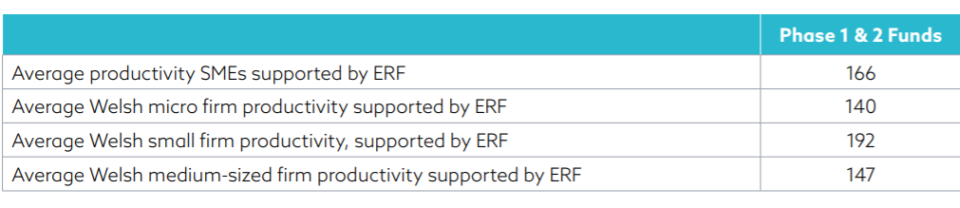

Analysis suggests that it was firms with lower productivity, particularly those of medium size (with between 50 and 249 employees), which found themselves drawing on emergency support the most (Table 1).

Figure 1: Seasonally adjusted quarter on quarter GDP growth

Source: ONS

Table 1: Reported sales per employee of Economic Resilience Fund (ERF) supported firms and averages for all firms in Wales

Source: Economic Intelligence Wales (2020)

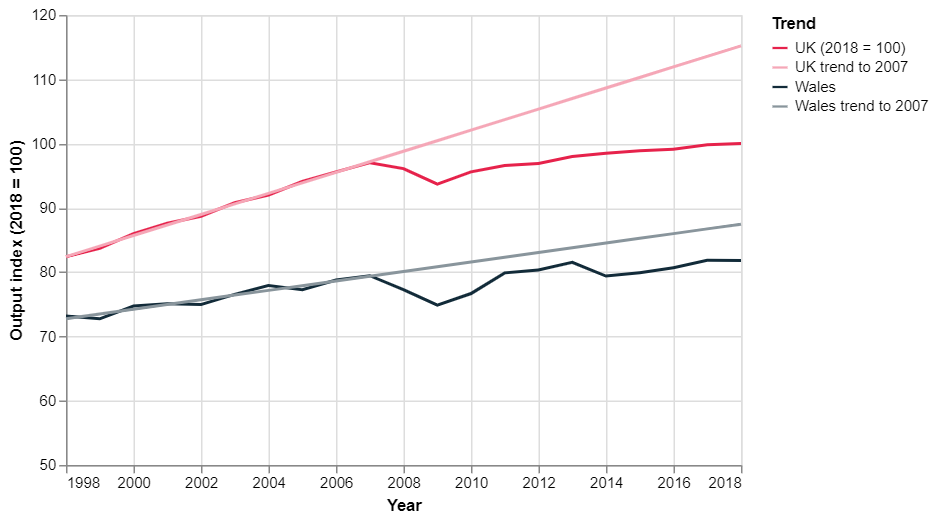

The Welsh prosperity gap has remained stubbornly persistent

The distance between Welsh productivity and that of the rest of the UK – the Welsh productivity gap (Figure 2) ¬– may be attributable to a range of sources, including differences in industrial structure (the relative absence of high value-adding service activity), skills gaps and lower levels of research and development (R&D). Low relative gross value added (GVA) – a standard measure of productivity – has meant that Wales has been eligible for three successive seven-year programmes of European structural funds support and has received around £4bn of additional funding in the final round in operation since 2014.

Figure 2: Output per worker in Wales and UK relative to trend

Source: computed from ONS published data.

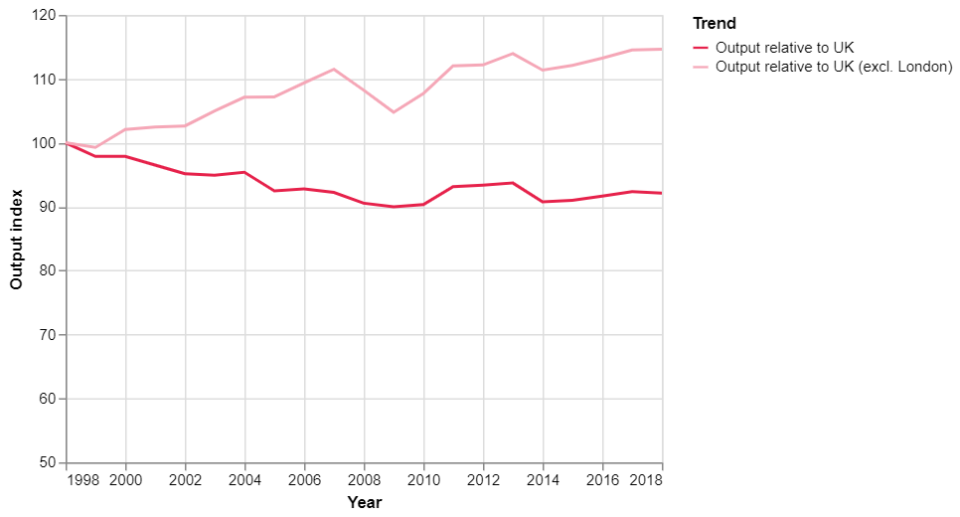

These support schemes may have allowed some closing of the productivity gap, but still leave a widening gap between Wales and London – see Figure 3. These interventions follow a range of objectives, including support for innovation, skills and improved digital infrastructure.

But business support schemes have typically been assessed in terms of job creation or safeguarding of existing jobs at risk of redundancy. They may have led to the protection of employment in lower productivity organisations or in lower productivity roles within organisations. Levels of private sector R&D expenditure in Wales remain at the lowest across all regions and nations of the UK.

Figure 3: Output per worker in Wales relative to the rest of the UK

Source: computed from ONS data

In the early years of devolved government, explicit targets for were set for Welsh productivity (measured as ‘GVA per head’) to catch up with the rest of the UK. But these targets were quickly abandoned as effective policies were difficult to design. It would be tempting to conclude that closing the productivity gap is now less of a priority for Welsh economic policy. And yet the WFGA defines a prosperous Wales as ‘an innovative, productive and low carbon society… which develops a skilled and well-educated population’ (Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, 2021).

But recent analysis from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation suggests that levels of poverty remain high in Wales, and the levels of in-work poverty remain among the highest across the UK (Matejic, 2020). The pandemic is likely to have worsened the situation, pressing home the priority of providing decent and secure employment and addressing barriers to employment such as affordable childcare. Further, the scale of the impacts of lockdown and furlough have also been felt unevenly across Wales and may have exacerbated existing differences between the larger cities, rural areas and Valleys communities.

Building back ‘better’, where ‘better’ means sustainable and inclusive

Many people across Wales agree that the post-Covid-19 recovery agenda needs to pay close attention to issues of job creation and social inclusion. The WGFA approach also highlights the importance of ensuring an alignment between shorter-term recovery goals and longer-term aspirations towards ‘clean’ growth (WCPP, 2020). The Welsh Government’s recent statement on economic recovery from the pandemic emphasises ‘prosperous’, ‘green’ and ‘equal’ as priorities (Welsh Government, 2021). But the specific details of recovery policies are unclear, and in some cases (for example, on innovation support) reliant on the uncertain generosity of the UK Shared Prosperity Fund.

A key feature of the current recovery plan, introduced in the Welsh Government’s earlier Prosperity for All strategy, is the notion of an ‘economic contract’ between business and government (Welsh Government, 2017). This would mean government support for business would be conditional on the implementation of actions to ensure fair pay and decent employment. This approach is predicated on the private sector in Wales viewing the contract as a welcome stimulus towards the creation of higher paid jobs supporting improved employee wellbeing.

Further, all of this needs to be set in the context of Wales’s relatively poor performance on R&D innovation. This is important because innovation is critical to the creation of high-paid, high value-added jobs (as well as stronger performance in new clean technology sectors). In this sense, there is no trade-off between productivity and sustainability.

To achieve this green growth, strict policy consistency is needed, and this will require Welsh Government ministers to take a more critical and selective approach, particularly in determining the type of manufacturing activity and jobs they seek to support with public funds.

As with elsewhere in the UK, commentary in Wales is focusing on the extent to which the pandemic might have accelerated or changed employment patterns and consumer behaviour, and the impact of these changes on different sectors.

It is of course too early to tell if changed patterns of commuting, remote working and access to shops will be permanent. For example, we do not yet know if the pandemic has led to permanent productivity-enhancing shifts in business models in service sectors or improvements in infrastructure congestion, air quality and carbon footprint.

Similarly, tourism, leisure and hospitality are all important sectors in Wales, which may experience a short-term bounce back as lockdown is eased. But firms in these sectors may also face increased longer-term uncertainties.

How can economic policy in Wales support inclusive productivity growth?

Productivity is influenced by a wide range of factors which affect business performance at a variety of levels. There is therefore a wide range of available policy instruments. The following are some specific priorities for Wales:

- Renewal of support for existing devolved competencies by the UK government, alongside appropriate levels of future funding under UK Shared Prosperity Funding to decision-makers in Wales.

- Further devolution of R&D and innovation funding, alongside institutional development of the Welsh innovation ecosystem to support improved private sector commitment to innovation in Wales.

- Improved articulation of skills needs by businesses, in the light of the post-pandemic business environment, to better match skills supply with demand.

- Clearer articulation of the logic of the Welsh ‘economic contract’ and the provisions of the Well-being of Future Generations approach in terms of their potential benefits for business.

- Better appreciation of ‘systems thinking’ in the coordination and policy mix of interventions to support productivity growth.

- Improved monitoring and evaluation of policy interventions supported by improvements in economic data on Wales and greater clarity in the ‘logic’ behind particular interventions.

This piece was first published in The Economics Observatory on May 6, 2021.