Investments in left-behind places will take time to boost growth

JOE PECK AND SAMUEL I THORPE

Can strategic investment bear fruit within a single election cycle? This remains one of the most important unanswered questions in the political economy of industrial policy. It is particularly pressing in the UK, as the current Labour government faces electoral challenges from the right and left. With Labour pinning its hopes on the Modern Industrial Strategy and investment-led growth, will Britons feel the benefits before the next election?

In new research published in the journal of the UK Academy of Social Sciences, we provide evidence on this question by studying the energy community tax credit in the United States. The US, like the UK, faces stark regional inequalities: median household incomes in its richest county (Loudoun County, Virginia; $170,463) are nearly 10 times higher than those in its poorest (Issaquena County, Mississippi; $17,900). Research suggests that these place-related differences persist across generations and deeply shape individuals’ ability to secure economic mobility. For many, simply moving places is not an option given the high economic costs involved; it also comes with risks, such as the loss of social capital.

The US energy community tax credit

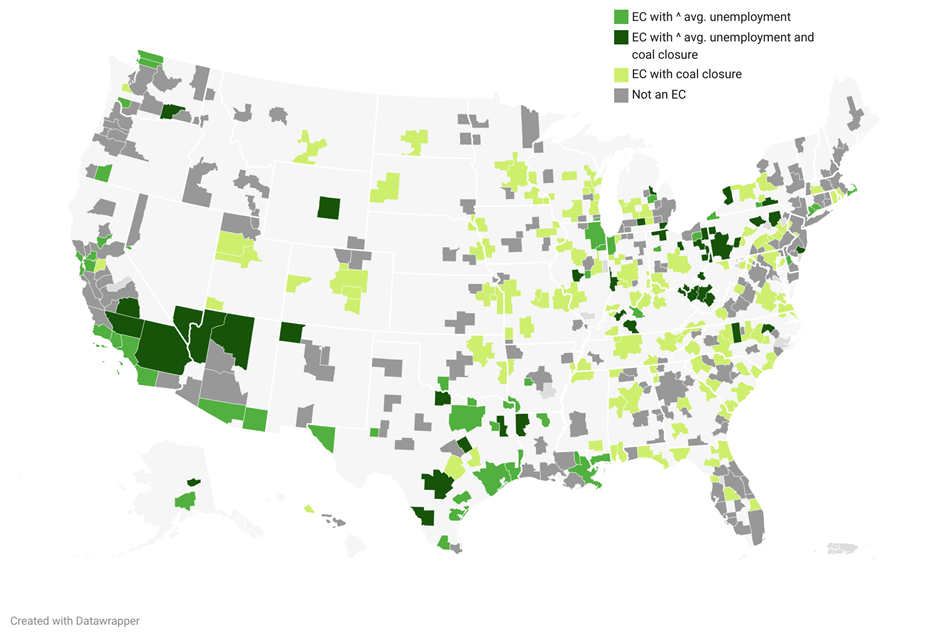

The energy community tax credit was intended to help bring investment to many ‘left-behind’ places in the US while simultaneously supporting the development of green energy. As part of the broader Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), the credit provided a substantial financial incentive for companies to invest in eligible areas (‘energy communities’), which have experienced the closure of a coal plant since 1999, or have suffered high unemployment rates while having significant employment in the coal, oil, and natural gas industries. Companies receive up to an additional 10% in electricity production tax credits if their facility is within an energy community. If a company invests in the production of batteries for electric cars, for example, they will receive a further 10% bonus for doing so in Zanesville, Ohio, as opposed to Newark, Ohio, by virtue of the former being an energy community. These tax credits resulted in cost reductions of more than 20% for solar projects in 2023; by some estimates, a standard 100 MW solar plant could benefit from more than $1.25 million in credits annually.

Figure 1: Locations of energy communities in the United States

Our research examines the effects of this credit on wages, unemployment, and labour force participation. While the credit did not have a statistically significant short-term effect in the vast majority of targeted regions, heavily-invested communities may have seen more meaningful impacts. Communities in the top quintile of investment – receiving more than $347, and in a handful of cases as high as $10,000, per capita – account for almost all of the measured change in these economic outcomes. This signals that larger amounts of funding could beget real economic changes within a politically-salient timeframe, in spite of the relatively weak basic and social infrastructure of struggling regions.

However, place-based industrial policy remains a slow lever for improving economic conditions for households in targeted regions. Effects on wages and employment remain small to non-existent on average even three years after the policy was passed and two years after it was implemented. This, along with the slow pace of the IRA’s implementation, provides at least a partial rationale for why these investments had a negligible effect on political support for the Democratic Party.

This does not suggest that this policy will continue to have an insignificant effect on regional economies in the medium to long run. Indeed, other evidence suggests that the long run impacts of place-based policy can be substantial. However, our paper highlights that industrial investments, even when targeted to specific communities, are unlikely to beget meaningful economic changes within a standard electoral cycle.

Implications for UK regional policy

The UK government’s current industrial strategy targets investment towards city regions and clusters where key industries are concentrated. The government hopes to achieve this through a combination of tax incentives and flexible spending awarded to Industrial Strategy Zones, alongside adjoining financial support like long-term, affordable loans to local authorities through the Public Works Loan Board and the £600m backing to the Strategic Sites Accelerator. While these are valuable parts of a long-term scheme to reverse regional decline, our results suggest that, if Labour is going to engage in an investment-led regional policy, it must prioritise moving quickly and investing deeply in specific communities.

Secondly, there is a risk that, in prioritising the places with the greatest potential for growth, the government will not strategically invest in the places with the greatest need. Even though the industries targeted in the UK government’s industrial strategy (the IS-8) are relatively well-distributed geographically, the government’s place-based industrial strategy is not explicitly focused on helping regions bearing the brunt of economic hardship complicating the UK’s path to more inclusive growth. Further, our results do not indicate that a need-blind approach to investment will prove fruitful, even in the short term: the US energy community tax credit was explicitly designed to boost growth in the regions that had suffered industrial decline. Our findings suggest this may be where they have proved most effective at boosting employment.

Ultimately, our findings suggest that place-based industrial policy is a slow tool for improving economic outcomes. Despite substantial evidence that investment has long-run impacts on growth, productivity, and wages, the energy community tax credit created few tangible benefits in most household-level outcomes within two years of its implementation. Where we do identify improvements, they are in communities which have received large amounts of investment and outcomes change only near the end of our period of study.

Our paper highlights two lessons. First, policymakers must make large investments as soon as possible to ensure the longer-term rewards of those investments become visible within a political cycle. Second, they will need to support communities and households in shorter-term and more tangible ways. Donald Trump’s victory in the 2024 election underscores a challenging political truth: voters do not reward politicians for promises of future growth. Feelings of ‘left-behindness’ recede only when economic change becomes visible in everyday life. With this lesson in mind, the UK government should not shy from investing heavily and quickly in the communities that need it the most.