Finance, Investment and Productivity Growth

Insights from research at the Bank of England and The Productivity Institute

By Catherine Mann, with contributions by the authors of the papers

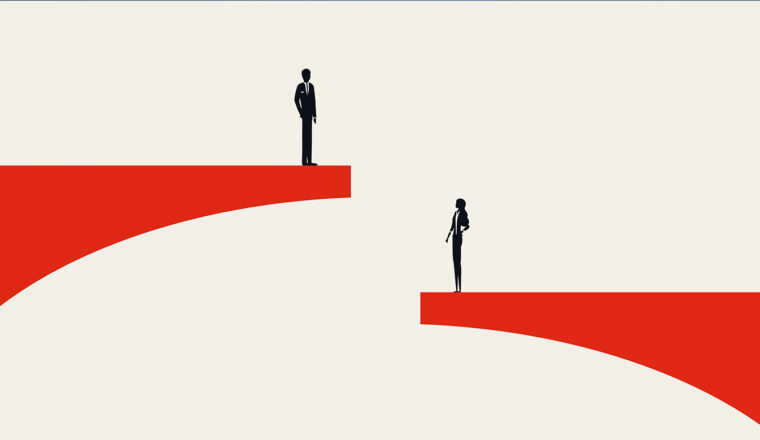

There is a long-standing view that UK firms exhibit short-termism and as a result they underinvest, contributing to low productivity growth. Previous research shows that UK investment, growth and productivity are substantially lower compared with a synthetic UK trajectory had the UK not experienced recent upheavals such as Brexit, COVID and the high inflation caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Key to the decision to invest – whether business or financial investment – are the cost of capital and the return on investment.

The Productivity Institute is focusing one of its research programmes on Finance, Investment and Productivity. A special session on the topic was organised for the 55th Conference of the Money, Macro and Finance Conference in September 2024 in Manchester. Two recent papers from the Bank of England and two pieces of research in progress at The Productivity Institute were presented.

Better than expected sales are positive for investment

Investment is a key driver of business dynamics and aggregate demand, but also plays a key role on the supply side of the economy, e.g. through supporting productivity growth. It is therefore important to understand how firms adjust their investment in response to changes in their economic environment, including the cost of finance and sales. Sales and investment likely drive each other, which makes it difficult to estimate the marginal propensity to invest (MPI) out of additional sales. In their paper, Firms’ Sales Expectation and Marginal Productivity to Invest: UK experience, Andrea Alati, Johannes J. Fischer, Maren Froemel (all Bank of England) and Ozgen Ozturk (Oxford University) use a novel approach – unexpected sales changes – to disentangle the two. The Decision Maker Panel (DMP), a representative survey of UK firms, allows to construct firms’ sales forecast errors and then estimate the MPI out of these unexpected sales changes.

The research finds that, while firms’ expectations are usually unbiased, they can be wrong. These ‘sales surprises’ convey information to learn about demand, and firms can act on that when deciding how much to invest. More attentive firms, proxied by their learning gain or pricing strategy, respond significantly stronger. Firms also increase prices after positive sales surprises, consistent with a demand-driven interpretation. The authors find a robust and significant MPI of 0.31 out of these sales surprises: a 1 percentage point higher than expected sales growth rate leads to a 0.31pp increase in capital expenditure.

The research suggests that the ability of firms to learn about changes in their environment is key for investment and growth. This highlights the importance for policymakers to design and communicate policies clearly and transparently. On the other hand, the authors find that financial constraints cannot explain their results, which implies that supporting dynamic businesses may require more than simply ensuring access to finance for capital investment.

Firms’ minimum required rate of return responds sluggishly to bank rate increases

A key channel by which monetary policy impacts the economy is through its effect on firms’ capital expenditure plans. In theory when policy rates are raised, business’ cost of capital also increases, and this higher cost of capital should lead firms to increase the minimum rate of return (or hurdle rate) required to undertake an investment project. A higher hurdle rate means fewer investments would be considered viable, and investment should decline. The implication is that for monetary policy to lower investment, changes in the cost of capital need to pass through to hurdle rates. The paper Evidence on the use and importance of corporate hurdle rates in the UK by Krishan Shah, Phil Bunn and Marko Melolinna (all Bank of England) uses a representative survey of UK firms (the Decision Maker Panel) to evaluate whether firms use hurdle rates and how these have changed as policy rates have risen sharply over the past two years.

The research finds that around 30% of firms set investment hurdle rates, and that these firms tend to be larger, more leveraged and operate in more tangible-intensive sectors of the economy than those firms that do not set hurdle rates. The average hurdle rate is higher than a firms’ cost of capital estimated using balance sheet data, and the median hurdle rate has only increased marginally, from 12% in 2018 to 14% in 2024. This, even as average rates on borrowing have increased by over 3 percentage points over the same period. Two factors are important to explain this sluggish adjustment: first, firms do not frequently adjust their hurdles rates; and second, when firms do adjust their hurdle rates, they pass through only around half the increase in their cost of borrowing into their hurdle rates. All told, this research suggests that changes in financial conditions only sluggishly enter the decision-making of managers to pursue new investment.

High-growth companies in the UK face sizeable funding gaps

Given the important role of high-growth enterprises in driving business innovation and boosting productivity, it is essential to understand whether these companies face any financial challenges that could impede their long-term investment and prevent them from realising their full potential. This question was the focus of the presentation by Viet Dang, Ning Gao, and Ruicong Liu (all Alliance Manchester Business School & The Productivity Institute) on Does the Equity Gap Matter? Evidence from High-growth Companies’ Investment. Leveraging a new dataset on fundraising activity for a large sample of UK high-growth companies between 2011 and 2022, the authors show that many companies raise significantly less equity finance than their peers. The authors’ conservative estimate suggests that those companies face a sizeable equity funding gap of £14 billion in 2021.

Importantly, this equity-financing gap significantly reduces high-growth companies’ investment by 30–40% on average and £3.4 billion in total, with the impact stronger still among companies that are already financially more constrained or those with ownership structures that are unattractive to equity investors. Surprisingly, while the impact of the equity-financing gap persists over a long horizon and remains significant in different industries and regions, there is limited evidence of the role of government capital injection in bridging such a gap. Ultimately, not only do companies facing funding challenges experience lower capital investment, but they also spend less on labour and show a lower degree of investment efficiency.

Overall, the findings demonstrate the important implications of external finance for company investment, highlighting the need to reduce the funding gap that could threaten long-term business viability. The authors call for further research to better understand what causes the equity-financing gap to inform corporate strategy and government policy.

The Global Financial Crisis caused a flight to safety solely to London and hinterland

Using a uniquely detailed dataset of real estate transactions, the presentation on City and Regional Risk-Pricing: The Geography of the Cost of Capital by Michiel Daams (University of Groningen), Philip McCann (University of Manchester & The Productivity Institute), Paolo Veneri (OECD) and Richard Barkham (CBRE) demonstrated that, prior to the 2008 crisis, investors were able to effectively price in risk across UK cities and regions. Both the observed risk premia and investment yields broadly followed textbook frameworks (see also Daams et al, 2023).

However, the onset of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis brought about a profound change in the capital market regime from an environment of risk, which could be effectively priced, to one of radical uncertainty, whereby investors were no longer able to do so (Daams et al. 2024a). This radical uncertainty engendered a rapid capital flight-to-safety in the UK (Daams et al. 2024a), the USA (Daams et al. 2024b) and the rest of Europe (Daams et al., TPI, forthcoming 2025). This flight-to-safety involved surges of capital inflows into clusters and central business districts within key ‘safe haven’ cities, but at the expense of other places.

In the case of the USA, this flight to safety was to some twenty large cities scattered across the country. In the UK, the flight-to-safety was solely to London and its immediate hinterland. London and its hinterland enjoyed surging capital inflows, a falling price of finance, and improved leveraging positions for real estate owners wishing to use real estate equity as collateral for entrepreneurial ventures and business investment. Other parts of the UK experienced capital flight, a rising price of finance, and deteriorating collateral positions. Places with falling costs of finance subsequently grew faster than places facing an increased cost of capital. City centres outside of the South East were the worst-hit places, and the capital markets’ segmentation of UK regions is currently on a continental wide scale, of the order of 250-300 basis points. Moreover, this segmentation appears to have been exacerbated by quantitative easing (QE). QE appears to only have benefited London, with the rest of the UK regions being almost entirely unresponsive to QE.

What have we learned and next steps

These four papers show the breadth of analysis engendered by looking at the relationships between finance and investment. Analysis can build on these papers to complete the assessment of how financial conditions affect productivity growth through the channel of investment. These papers do move us forward substantially in understanding of some of these relationships; but also raise a key question – how much does finance really matter?

The paper on sales surprises emphasises that financial constraints do not explain differences in investment across firms. The hurdle rate paper implies that investment only sluggishly responds to changes in the cost of capital. Yet the equity-financing gap points to significant losses of investment potential from insufficient finance. And the flight-to-capital paper finds a key role for capital flows to affect outcomes in cities and regions outside London. The central role for finance in investment and follow on to productivity growth has not been resolved. There clearly are other factors that affect the investment decisions and outcomes.

Digging deeper into the dynamics of the marketplace, including market growth, a firm’s market power and information uncertainty and economic risk are directions for further research on investment and its link to productivity growth. Other research, which has less focus on the cost-of-capital, finds growing markets (including global markets) and those with lower uncertainty and risk (say from policies and politics) complement financial conditions. The relationship between firms that enjoy concentrated market power and their investment or productivity growth is less clear. Marrying the work here that focuses on variations in the cost and availability of finance with research that concentrates on markets would be valuable, of course using firm-level data that is de rigour for this kind of analysis.

Furthermore, there is a missing actor in these papers – managers of the firms and managers of investable capital (e.g. financiers). As outlined in the TPI paper UK Business Investment: Economists, Managers, Financiers An Integrated Framework to Analyse the Past and Underpin Prospects, it is the intersection of economic drivers (cost of capital, sales, risk and uncertainty) with the objectives of managers (through compensation plans or to align objectives within different divisions of firms) and with the objectives of financial investors (including portfolio strategy) that ultimately determines investment decisions at the firm level, collectively for the macroeconomy with understanding the drivers of productivity growth the end goal.

By Catherine Mann, with thanks to the authors of the papers