Uber and the broader gig economy vs productivity

The recent UK court victory by some Uber drivers raises broader questions about the future of what is often described as the ‘gig economy’. Although the court’s decision affects only Uber directly, it has potentially big implications for a large group of workers, and for productivity.

In the latest policy brief from the Productivity Institute: Uber And Beyond: Policy Implications for the UK, Abi Adams-Prassl and Jeremias Adams-Prassl of the University of Oxford and Diane Coyle of the University of Cambridge (and a member of our Executive Team) discuss the implications of the judgement.

In March 2021, the UK Supreme Court unanimously agreed that drivers from transportation network company, Uber were not genuinely self-employed, and thus were entitled to the full set of rights and protections associated with their new status as ‘workers’ (an intermediate category between employees and self-employment). Uber CEO Dara Khosrowshahi responded: “Uber drivers in the UK will be treated as workers, they will receive holiday pay and will be guaranteed at least the National Living Wage (as a floor, not a ceiling, meaning they will be able to earn more.) And eligible drivers who want a pension will receive one.”

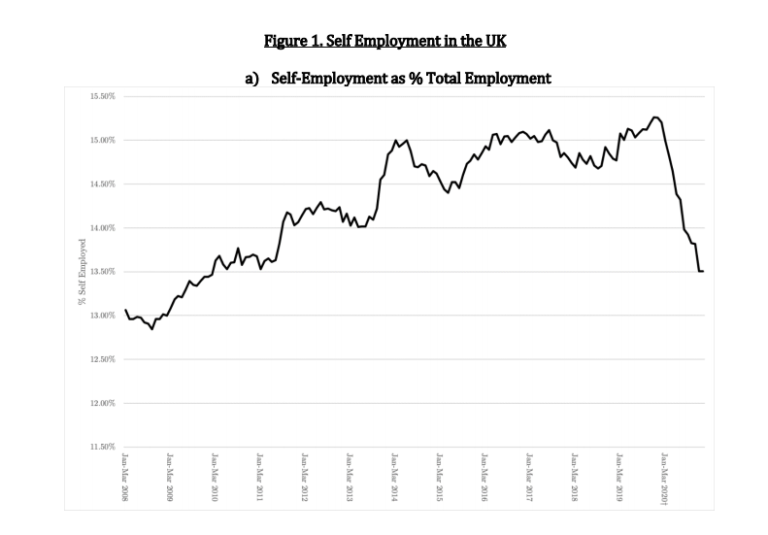

But the focus on Uber or even just digital platforms overlooks the fact that a much larger group of people in the UK have insecure work, whether it is zero hours contracts, solo self-employment or short term contracts. Altogether, it amounts to about one quarter of the workforce. They often have little control over their hours of work – it is the employers who enjoy all the benefits of flexibility. Self-employment, and solo self-employment in particular, rose dramatically between the financial crisis and the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Self-employed or employees?

As the policy brief discusses, there are benefits of flexibility in working via digital platforms like Uber, for example for drivers from ethnic minorities or from disadvantaged areas. A majority of workers are happy with self-employment and value flexibility. However there is also a group – young men with low educational qualifications – who are dissatisfied and self-employed because of a lack of alternative options.

Figure 1 shows the rise in self-employment since the financial crisis and its dramatic drop during the pandemic.

Although the new judgement now classes Uber drivers as workers, providing them with basic rights including the national minimum wage and paid annual leave, they have many attributes of being self-employed.

But the traditional gig economy model does not allow all workers to choose when and how they work. Instead it gives them the opportunity to make themselves available to work if there is sufficient customer demand – a long way from two-sided flexibility.

In fact the brief shows that many of those in the gig economy are closer to the “necessity” model of self-employment. 80% of gig workers use any jobs they receive to top-up their income from other sources or in response to the current pandemic.

The impact on UK productivity

The ‘monopsony’ power of the digital platforms and some other employers means their workers do not have a wide choice of occupation. The widespread, one-sided flexibility of the UK labour market has locked in a low productivity mode of work. People whose earnings are often low and insecure do not have either the money or the incentive to invest in their skills or in equipment. The policy brief also points out wider implications. For example, the platform model means the tax base has been diminished because most ‘gig’ employees do not earn enough to pay VAT. Most of the workers concerned do not have a pension or savings, with long term implications for the health of the welfare state. A further issue is the lack of enforcement of the labour market regulations meant to protect workers. There have now been a series of judgements affirming workers’ rights but unless they are enforced, the low productivity model in the UK jobs market will continue.

This blog is based on the Productivity Insight Paper Uber and Beyond: Policy implications for the UK.