Redefining public sector productivity

Recent government efforts toward improving public sector productivity, including Chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s Spring Budget ‘public sector productivity drive’, are marked by a focus on cost-efficiency, missing an opportunity to introduce other innovation-enhancing measures to the sector, write Ayantola Alayande and Lucy Hampton based on a new Productivity Insights Paper with Nina Jörden.

Improving public sector productivity has been a top priority for the UK government lately. Both Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and Michael Gove, Levelling Up Secretary, have articulated this commitment in several ways. For instance, Mr Hunt’s 2024 Spring Budget announcement included a public sector ‘productivity drive’ aiming to return public service delivery to its pre-pandemic levels and deliver more than £20 billion in savings per year. This comes in addition to his 2023 launch of a public sector-wide productivity review and Mr Gove’s allocation of an additional 600 million pounds to enhance service delivery in local councils in 2024.

However, these efforts have been marked by a focus on cost-efficiency – illustrated by targets such as ‘delivering savings’ and ‘eliminating waste in the system’. Our new paper argues that such sole focus on efficiency and cost savings comes with inherent risks, including reduced service quality, a pressured workforce, and missed opportunities for innovation.

Why is public sector productivity important?

Different government units (e.g. local versus national) have distinct goals, as well as varying service delivery models, including ‘allocative services’ (those paid for and used by the same group of people), ‘redistributive services’ (progressive tax-funded welfare or social security interventions), and developmental services (funded through government subsidisation of private sector activities). While public sector productivity is often viewed in terms of the delivery of essential services such as education, healthcare, and infrastructure, it also includes less tangible outcomes such as ensuring economic stability that provides an enabling environment for private sector growth, emergency preparedness, and regulatory oversight. This multifaceted outlook of the public sector raises a concern about how to define and measure productivity in such a complex context.

Defining and measuring public sector productivity

At its core, productivity is how much output is produced relative to the inputs used. Different productivity concepts correspond to the inputs in question: worker-hours for labour productivity, for instance, and all measured inputs for multi-factor productivity.

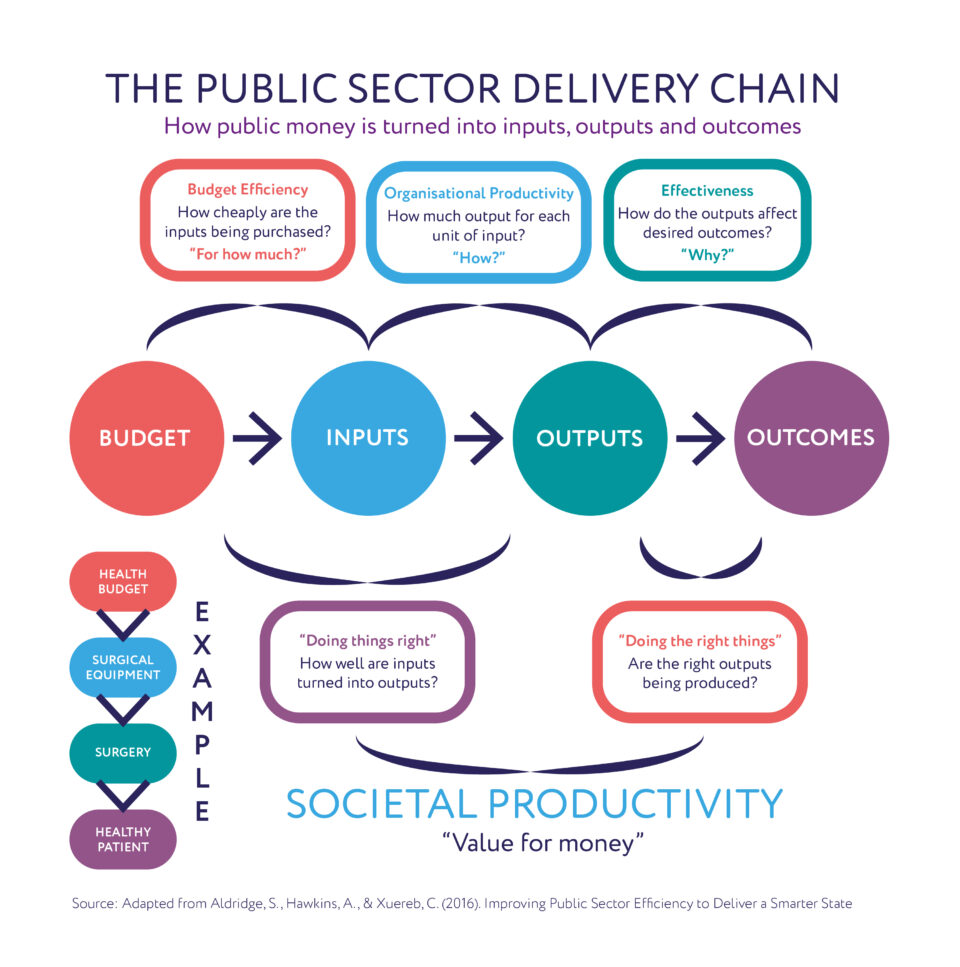

We argue that the concept of ‘output’ in the public sector is fundamentally different to that of the private sector. While private organisations’ (primary) goal is to maximise profit, public sector organisations ultimately aim at broader social outcomes (e.g. increasing education levels), as well as more immediate outputs (e.g. a certain level of GCSE attainment). Therefore, different concepts of productivity emerge based on the stage of the public sector delivery chain, as shown in the diagram. Simply adopting the same concept of productivity as the private sector could lead to a narrow focus on budget efficiency and organisational productivity (i.e. ‘doing things right’) at the exclusion of effectiveness (‘doing the right thing’).

Source: van Ark, 2022

The idea that we can measure public sector productivity growth at all is relatively new. Initially, productivity was estimated via an ‘inputs = outputs’ approach, which implies zero productivity growth. This changed following the Atkinson Review in 2005, which aimed to make public sector productivity measurement more consistent with the private sector. Even so, 40% of public sector services by expenditure are still estimated on an input = output basis, including key services like policing, justice and defence.

So, why is productivity in the public sector so hard to measure? We suggest some reasons in the report:

- Many public sector organisations have preventative roles – e.g., the fire services aim to prevent as well as tackle fires. It is important that both the benefits of preventative activities are recorded as outputs, and that the outcomes that they aim to prevent are not.

- It is difficult to attribute social outcomes to specific public sector organisations. This is partly because they may be influenced by the broader social and economic environment, and because different organisations affect the same outcomes.

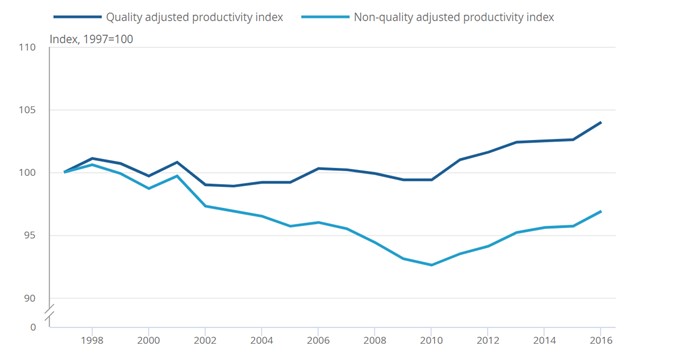

- Quality-adjusting outputs and inputs is much harder in the public sector due to the absence of prices at the point of delivery. Currently, fewer than two-thirds of productivity measures in government services are quality-adjusted, however, quality-adjustment can have a significant impact on headline statistics as the graph below shows.

- The data required often do not exist or are not timely or detailed enough.

Figure 2: Non-quality-adjusted productivity falls over the time series, but quality-adjusted productivity increases, with a stronger divergence as time goes on.

Source: Office for National Statistics – Public service productivity total: UK, 2016

The Office for National Statistics’ (ONS) public sector productivity review demonstrates this, but progress is being made on improving measurement across services, especially quality adjustment.

Public sector productivity in practice: What are the options?

Our report highlights two key options for boosting public sector productivity: digital transformation and management practices.

Digital transformation

Despite much optimism around the potential of technology to transform public service delivery, scepticism abounds due to the plethora of failed digitisation projects. Nonetheless, our paper highlights a success story with crucial lessons – the case of ResilienceDirect (discussed by Sage et al., 2022), introduced by the UK Cabinet Office in 2014 as a collaborative platform for emergency management among multiple government agencies.

One major lesson with the use of ResilienceDirect during the pandemic is the need to view technology as an ever-changing phenomenon. This requires readiness to embrace flexibility in managing conflicting viewpoints and the friction between innovation and stability or between efficiency and quality improvements. Other takeaways both from the more successful ResilienceDirect case and the non-successful projects include:

- Understanding that there might be a time lag (the productivity J-curve) between the adoption of a new digital initiative and the realisation of productivity gains calls for taking a long-term view toward investment in new digital initiatives.

- Organisational change – including fostering digital readiness and skills development, an agile workforce, and a data-centric culture – is essential.

- A well-defined data policy is crucial for the efficient utilisation of public service data and for enabling the private sector to derive additional service value from such data.

- Increased outsourcing of public sector IT projects might stymie public sector development of its own capacity, limit organisational flexibility, and hinder the agility to adapt to changing circumstances of digital integration swiftly.

Management practices

Recent studies focusing on the private sector have highlighted the importance of management practices for productivity. Management may be even more important in the public sector due to resource constraints and greater public scrutiny.

Of course, not all management practices implemented in the private sector are suitable in the public sector. Financial incentives for instance may be infeasible due to budget cuts, hard to implement due to the difficulty of measuring the goals to tie incentives, and may be seen as an inappropriate use of taxpayer money.

More important is developing an ‘agile workforce’ in which workers have the flexibility to proactively come up with solutions and continuously learn from results. This is especially important at a time of significant technological, financial and workforce disruption – agile workforces are also resilient ones. It also complements digital transformation initiatives, given the crucial importance (as argued above) of developing digital skills throughout an organisation, swiftly communicating new techniques, and learning when projects fail.

Concretely, how can workforce agility be cultivated? The human resources department plays a crucial role here in identifying skills gaps and following up with training programmes or external skills acquisition (e.g. through consultants). One recent example is the civil service’s Central Digital Data and Data Office which conducted a survey in 2022 to understand digital skills capabilities across government and civil servants’ views on the importance of digital skills. This was followed by a pilot of a Digital Excellence Programme (DEP) to support senior civil servants in building a digital culture in government.

Conclusion

Increasing public sector productivity requires not only practical interventions but also a better understanding of how it should be defined and measured. Neglecting the unique structure of the public service delivery chain leads to a fixation on cost-cutting, the benefits of which, we argue, have reached their limit. Sustained productivity improvements will require a longer-term approach. This includes investment not just in new digital tools but also in the skills, culture and management practices required to benefit from them.