Identifying Industrial Renewal Paths of Places for Levelling Up

This blog written by Enrico Vanino (University of Sheffield) presents the key findings from a report on Identifying Places Industrial Renewal Paths in the UK and the underlying data dashboard, developed during his academic secondment at the Cities and Local Growth Analysis Unit in BEIS funded by ESRC.

Productivity is the main driver of economic growth and determines the long-term economic success of a country. The UK has a longstanding productivity gap with its major competitors (ONS, 2018), with large spatial disparities across places, driven by London’s outstanding role as a highly productive global city, while a large number of regions are lagging behind with low productivity levels (ONS, 2021). These regional disparities in economic performance are large, persistent and have widened over time, making the UK one of the most spatially unequal countries in the OECD (Martin et al., 2016; McCann, 2020). Reducing regional productivity disparities through a stronger catch up of regions outside London could address part of the UK productivity gap, ensuring economic growth and prosperity across the UK.

Regional Productivity Differences and the Local Industrial Structure of Places

Several factors have been identified as potential drivers of spatial productivity imbalances across the UK, including infrastructure investment, human capital, institutional governance and the local business environment. Differences in the local industrial structure could account for a substantial share of regional differences in productivity, both in terms of differences in industrial mix and within-industry productivity across regions. For instance, recent findings show that the median firm performs similarly across the country within sectors, while differences in average regional productivity are driven by the “happy few”, larger, more productive, internationalised, more skill and innovation intensive firms mostly located in South-East (ERC, 2020). In this case, industrial policies should focus on promoting upscaling and upskilling of laggards in order to level up the country.

However, despite regional sectoral compositions looking similar at the aggregate level (ONS, 2019; ISC, 2020), there is growing evidence that the local industrial mix is significantly different between regions at the sub-sectoral level, since the most productive tasks within the same broad industry are clustered in the most productive places (Duranton and Puga, 2005; Coyle and Rosewell, 2015; Mealy and Coyle, 2021). For instance, in a recent study looking at 700 industries across 175 areas in the UK (Corradini and Vanino, 2021), we have shown that local industrial path dependence fosters entrepreneurship in rooted existing industries, while hindering economic activities in pioneering industries new to the region. However, the presence of a mix of different unrelated sectors within a region could counterbalance the role of industrial path dependence, supporting the emergence of pioneering sectors new to the region. Policy interventions could therefore build on local capabilities and comparative advantages to enable industrial transition and branching, promoting incremental diversification towards higher added-value related sectors.

Smart Specialisation Strategies and Levelling Up

The possibility to recombine existing knowledge and skills to support new productive trajectories has been the main focus of the smart specialisation strategy, a vision of regional growth built around existing place-based capabilities (Barca, 2009; Foray et al., 2009; McCann and Ortega-Argilés, 2015; Balland et al., 2019). The main goal of smart specialisation is to leverage existing strengths, identify hidden opportunities, and generate novel platforms upon which regions can build competitive advantage in high value-added activities. This contrasts with “one-size-fits-all” policies developed at the national level and other generalist industrial strategies, which prioritise high-technology sectors over all others (David et al., 2009). In fact, while the presence of novel technologies and innovative high-tech start-ups are essential for the creation of new industrial paths defining leading regions, path renewal and path extension can be more effective in lagging regions, helping them to diversify and become more resilient to economic crisis (Grillitsch et al., 2018; Isaksen et al., 2018; Corradini and Vanino, 2021).

We apply insights from the smart specialisation strategy framework to the UK to identify possible venues for economic diversification and new industrial paths for places across the country. To achieve this, we follow the established stream of economic complexity and relatedness research (Hidalgo et al., 2007; Hidalgo and Hausmann, 2009; Neffke et al., 2011), starting by identifying existing capabilities and industrial comparative advantages of places across the UK. We then develop a measure of relatedness between industries using data on employment at the granular level of sub-sectors (SIC4) and Travel to Work Areas (TTWAs), which allow us to estimate the relatedness density of each sector to the local existing industrial portfolio. Relatedness density represents the strength of an industry’s connection with all the other industries in which a locality has comparative advantage, in terms of production processes, input-output linkages, technologies adopted, or skills required. Combining this analysis with data on industrial productivity, we develop a new index of local industrial renewal path, identifying opportunities for new industrial trajectories for places based on their existing capabilities and relatedness with new highly productive industries.

Industrial Renewal Paths of Places across the UK

Our analysis suggests that a defined set of sectors feature among the top industries in terms of the local industrial renewal path index for several TTWAs across the country. These include the motion picture, video and television programme distribution sector, the manufacture of synthetic rubber, the wholesale of information and telecommunication equipment, the leasing of intellectual property, and the coastal passenger water transport. Our evidence highlights how these industries could serve as viable diversification paths towards higher-productivity sectors for many different places across the UK.

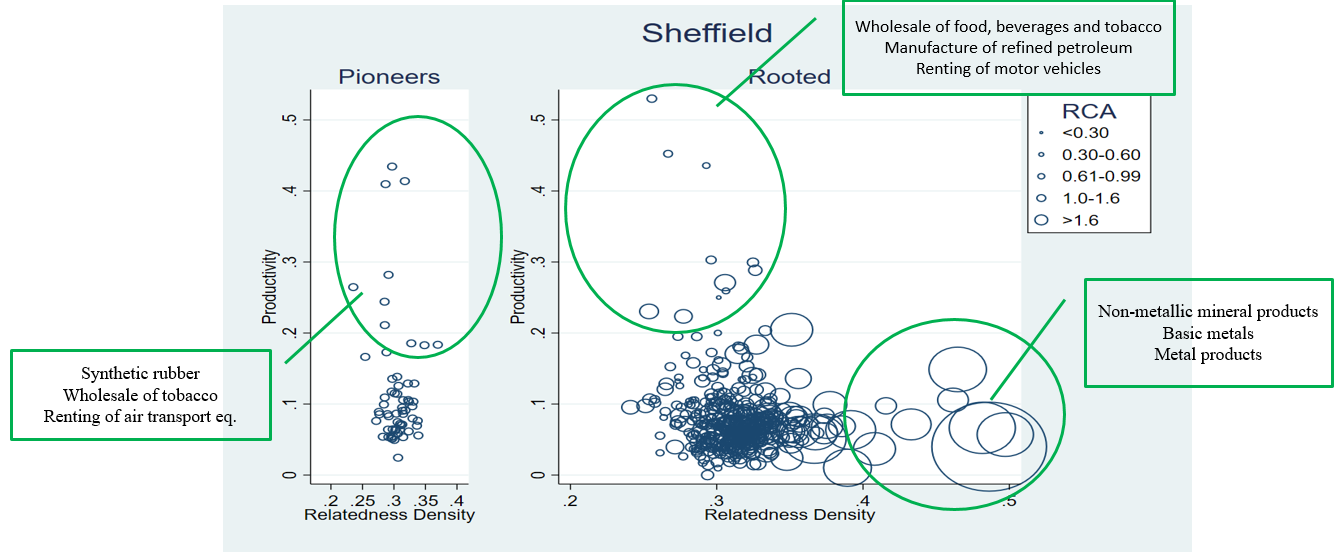

Figure 1: Industrial renewal paths in Sheffield in rooted and pioneering industries.

Notes: Elaboration based on employment data at the TTWA and SIC4 industry level for the period 2015-2019 from NOMIS ONS Official Labour Market Statistics and on productivity data at the SIC4 industry level based on gross value added (GVA) for the period 2015-2019 from ONS Annual Business Survey (except financial sector). Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) measured for each TTWA and industry based on the Balassa Index (Balassa, 1965; French, 2017) as the relative share of an industry in the total employment of the TTWA, compared with the relative importance of the industry in the UK total employment. Relatedness density measured as the relatedness of an industry to all other sectors in which the TTWA has a comparative advantage, divided by the sum of the relatedness of an industry to all the other sectors in the UK. Relatedness density and productivity measures are normalised between 0 and 1. Rooted industries are defined as pre-existing industries, while pioneers are industries not operating in the region yet.

We also identify local industrial renewal paths for specific TTWAs based on the relatedness density, productivity and revealed comparative advantages of their local industrial structures. For instance, Figure 1 shows how the Sheffield area is mostly specialised in low productivity sectors, such as those in the manufacture of non-metallic mineral products, basic metals and metal products. There are a few existing sectors within the TTWA (rooted industries) with high relatedness density and high productivity,, like the wholesale of food, beverages and tobacco, the manufacture of refined petroleum products, and the renting and leasing of motor vehicles. In addition, other pioneering industries not yet present in the region represent promising opportunities for local renewal path based on their relatedness with the existing sectoral structure and their high levels of productivity, such as the manufacture of synthetic rubber and the renting of air transport equipment.

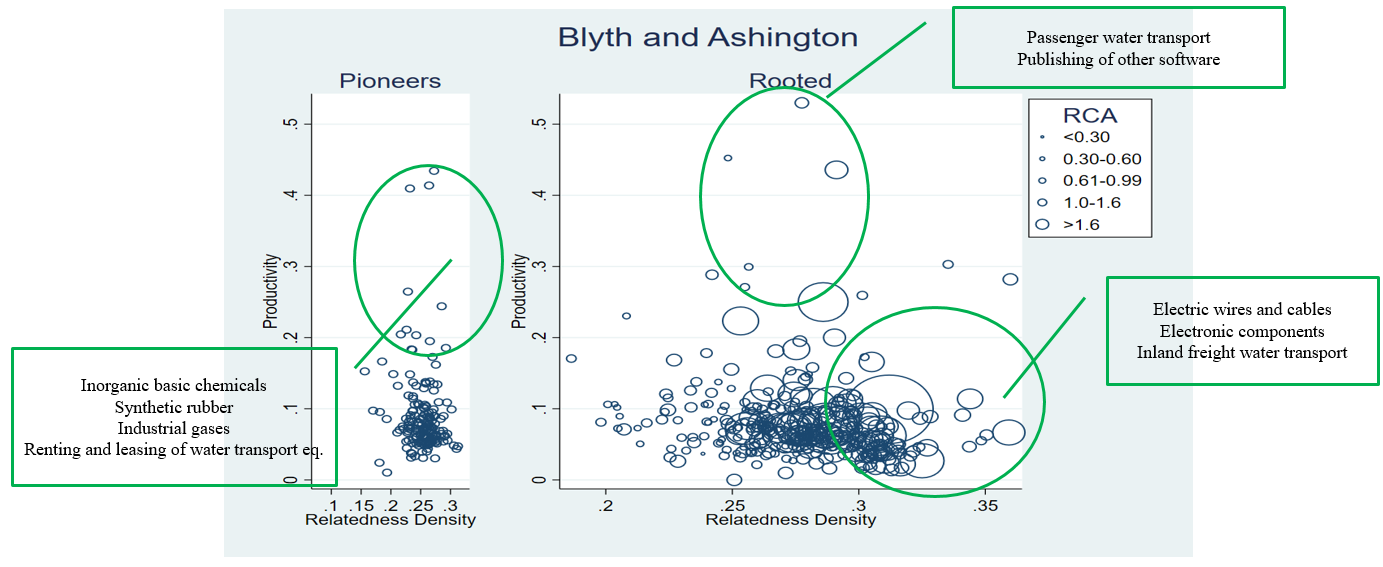

Another example is Blyth and Ashington in Figure 2, a TTWA negatively affected by deindustrialisation in Northumberland, which is now experiencing an industrial revival thanks to the development of the offshore wind energy industry. The area is in fact specialised in several manufacturing industries, such as the production of electric wires and cables, the manufacture of other electronic components, and inland freight water transport services. Given its industrial mix, a few promising rooted services industries include the sea and coastal passenger water transport, and the publishing of software. Diversification into new pioneering industries could also be strongly linked to the existing industrial mix, like the manufacture of inorganic basic chemicals, synthetic rubber and industrial gases, sea and coastal freight water transport services, and the renting and leasing of water transport equipment.

Figure 2: Industrial renewal paths in Blyth and Ashington in rooted and pioneering industries

Notes: Elaboration based on employment data at the TTWA and SIC4 industry level for the period 2015-2019 from NOMIS ONS Official Labour Market Statistics and on productivity data at the SIC4 industry level based on gross value added (GVA) for the period 2015-2019 from ONS Annual Business Survey (except financial sector). Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) measured for each TTWA and industry based on the Balassa Index (Balassa, 1965; French, 2017) as the relative share of an industry in the total employment of the TTWA, compared with the relative importance of the industry in the UK total employment. Relatedness density measured as the relatedness of an industry to all other sectors in which the TTWA has a comparative advantage, divided by the sum of the relatedness of an industry to all the other sectors in the UK. Relatedness density and productivity measures are normalised between 0 and 1. Rooted industries are defined as pre-existing industries, while pioneers are industries not operating in the region yet.

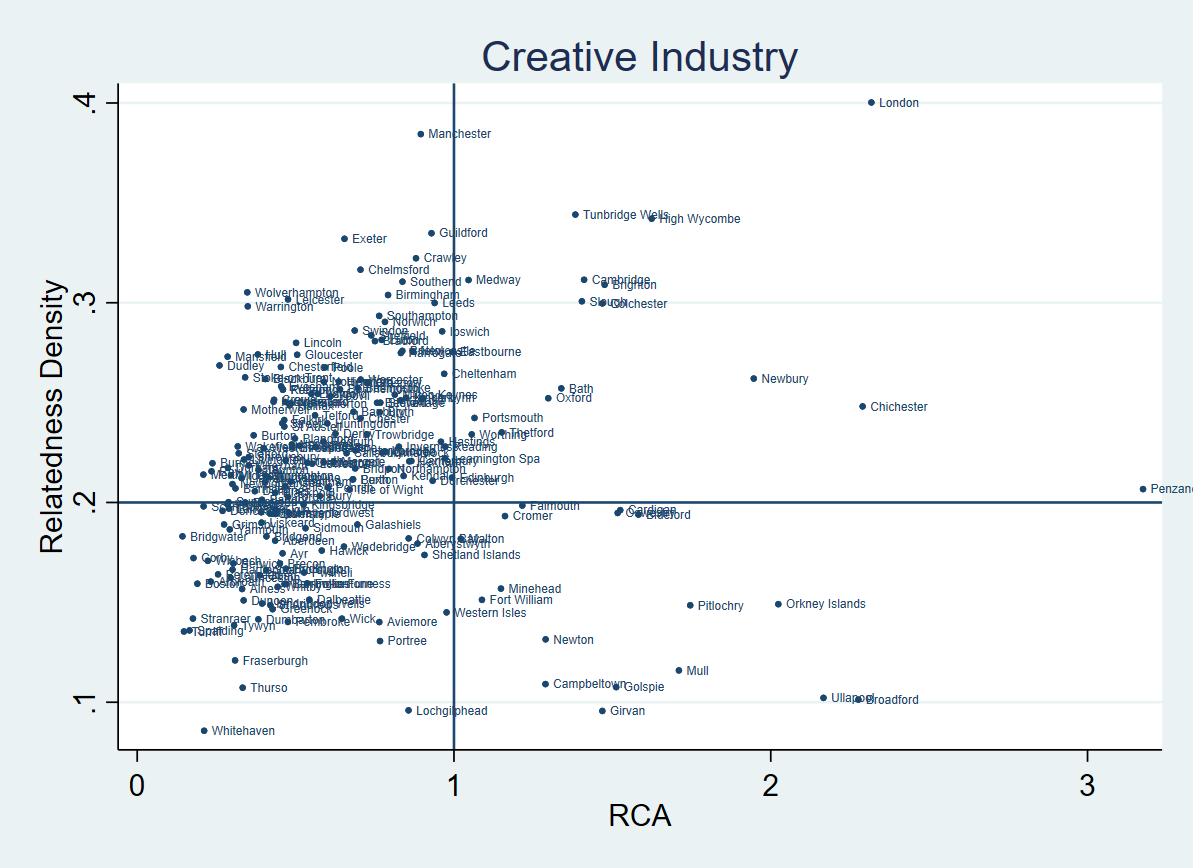

Finally, this analysis can also be used to identify the best locations for the development of key industries targeted by the UK Government Plan for Growth (2021) as vital for the future economic development of the country, based on their relatedness density with the rest of the local economic structure and the revealed comparative advantage of TTWAs in these sectors. Figure 3 presents the case of creative industries, among the most internationally competitive UK industries. We notice that not many TTWAs exhibit strong comparative advantages in these industries, which are mainly clustered in Penzance, London, Chichester, Newbury, High Wycombe, Brighton, Cambridge, Bath and Oxford. However, we can see that other TTWAs in the top left corner of the diagram could be ideal locations for the development of creative industries, as they show strong relatedness density with the existing industrial structure, as the case of Manchester, Guilford, Exeter, Crawley and Leicester.

Figure 3: Relatedness density and RCA of TTWAs in the creative industries

Notes: Elaboration based on employment data at the TTWA and SIC4 industry level for the period 2015-2019 from NOMIS ONS Official Labour Market Statistics. Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) measured for each TTWA and industry based on the Balassa Index (Balassa, 1965; French, 2017) as the relative share of an industry in the total employment of the TTWA, compared with the relative importance of the industry in the UK total employment. Relatedness density measured as the relatedness of an industry to all other sectors in which the TTWA has a comparative advantage, divided by the sum of the relatedness of an industry to all the other sectors in the UK. Relatedness density is normalised between 0 and 1.

The recombination of existing knowledge and skills to support new productive trajectories could offer a viable strategy to improve competitiveness, promote economic diversification and resilience across places. Smart specialisation strategies promote a vision of regional growth possibilities built around existing place-based capabilities, trying to leverage existing strengths, identify hidden opportunities, and generate novel platforms upon which regions can build competitive advantage in higher value-added activities. The study of places’ industrial renewal paths provides an additional source of analysis, which combined with previous evidence could help policymakers reduce regional productivity disparities in the UK, ensure economic growth and prosperity for all, and help level up the country.